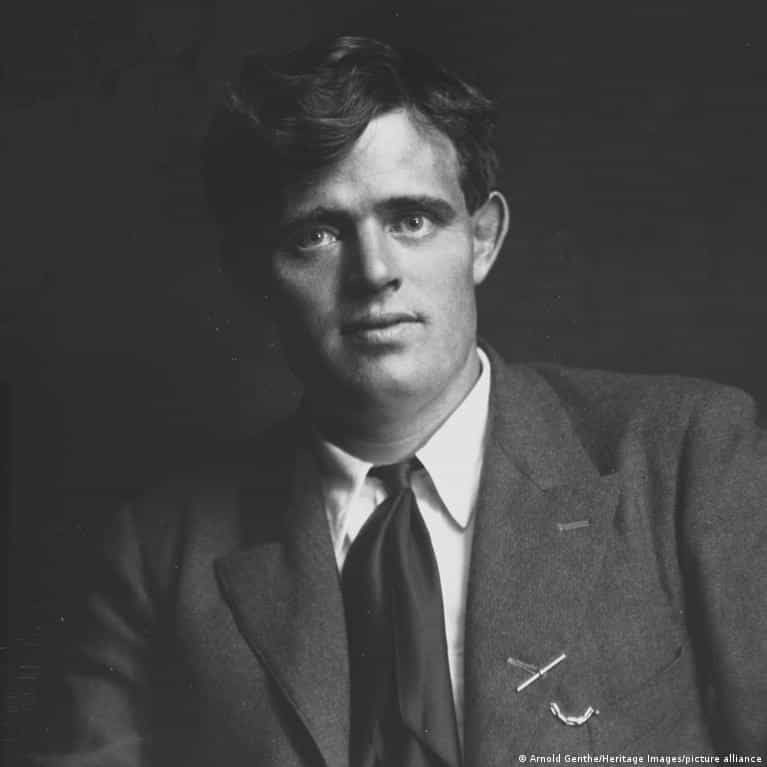

Born in San Francisco as John Griffith Chaney on January 12, 1876, Jack London lived a life even more dramatic than those portrayed in many of his novels. His biological father never acknowledged paternity, shunning his mother while she was still pregnant. She would later marry Civil War veteran John London, who took him in as his stepson and gave him his surname.

London grew up in severe financial hardship. From an early age, he left school and took up multiple jobs to help support his family. He earned money as a paper boy and worked in saloons and factories. As a teenager, he illegally harvested oysters in the San Francisco Bay before jumping sides to join the San Francisco Bay fishery patrol, where he pursued illegal oyster harvesters such as himself. At age 17, he worked on a seal hunting ship that sailed around Japan and the South Pacific.

Those experiences shaped his worldview, as did reading, which fascinated him from childhood. London began writing about what he knew and had lived through. An early piece about his time aboard a sealing ship won first prize from the "San Francisco Call" newspaper.

London kept pursuing adventure, joining unemployed workers as they marched across the United States toward Washington. He lived as a drifter, spent 30 days in jail, and at age 20 finally enrolled in college. After just one semester, he quit. Jack London simply wanted to write.

That wasn't paying the bills, though, and he returned to hard labor, shoveling coal at a power plant. There, he experienced the dark side of capitalism: The exploitation of labor, with workers pushed to their limits for ever-shrinking wages. He continued his self-education, reading thinkers such as Karl Marx and Charles Darwin, and developed a strong political consciousness that he later expressed through his writing and public advocacy.

News of gold discoveries in the Klondike region of Canada swept across North America, and like many others, Jack London was caught up in the gold fever and had big dreams of striking gold in the Dawson City, in the Canadian territory of Yukon. In the summer of 1897, he headed north with a group of adventurers, traveling through Alaska and over steep mountain passes such as the Chilkoot Pass. He later journeyed by boat along the Yukon River, hoping to reach the Klondike, where rumors spoke of fist-sized gold nuggets.

The search for gold proved fruitless. Stricken with scurvy, London was eventually forced to return to California in 1898, penniless but rich in experiences that would later fuel his writing. What he did have by then, though, was a wealth of experience — which he now began to put to paper. After rounds of rejections, his first collection of short stories was finally published. His work struck a nerve at the end of the 19th century. His first-hand depiction of the brutal Arctic winter, untamed nature, and the longing for the unknown — for extraordinary people and wild animals — became a major success.

His international breakthrough came in 1903 with "The Call of the Wild" — the story of a kidnapped dog that rediscovers its instincts in the Alaskan wilderness. He followed up with "The Sea Wolf" in 1904 and "White Fang" in 1906— another classic that redefined the relationship between humans and animals in a harsh and hostile environment.

London was more than an adventure writer; he was also a keen observer of society. In his 1903 "The People of the Abyss," he documented the extreme poverty of London's East End. Dressed in ragged clothes, he went undercover in the slums there for seven weeks, posing as a day laborer.

His account of the time describes dark, foul-smelling alleys, unimaginable deprivation, and children growing up among beggars, drunks, thugs and pimps. The piece he created from his experiences is viewed as a forerunner of modern investigative journalism.

London was a socialist. He criticized exploitation and child labor and believed society could be changed. At the same time, he was also shaped by the attitudes of his era. Today, his racist views and social Darwinist belief of "the survival of the fittest" are rightly viewed with a critical eye.

London wrote over 50 books, as well as countless short stories and journalistic reports. A self-taught writer, he became a literary star — one of the first authors in the world to earn a living solely from their writing.

He set himself a strict rule: 1,000 words a day, regardless of his condition or location. Yet he paid a high price and struggled with alcohol abuse and recurring health issues.

London died in 1916 on his ranch in California at age 40. The exact cause of his death remains the subject of much speculation.

His stories of survival in an unpredictable world feel strikingly relevant in the 21st century. His characters battle natural forces, social injustice and inner demons. They rarely represent simple heroism, instead embodying the struggle for identity and humanity.

London's view of the wilderness was respectful, but unsentimental. In his work, nature is neither a romantic idyll nor a decorative backdrop. It's a powerful force — raw and merciless, yet fragile. In the age of climate change, it's a perspective that seems almost prophetic.

Now, 150 years after his birth, Jack London remains a contradictory and compelling figure: Adventurer, working-class child, social critic and novelist. His books show that stories can do more than entertain — they can help explain the world. Some of the questions he raised in his time still burn bright today.

This article was translated from German.

Editorial Context & Insight

Original analysis and synthesis with multi-source verification

Methodology

This article includes original analysis and synthesis from our editorial team, cross-referenced with multiple primary sources to ensure depth, accuracy, and balanced perspective. All claims are fact-checked and verified before publication.

Primary Source

Verified Source

Deutsche Welle

Editorial Team

Senior Editor

Shiv Shakti Mishra

Specializes in World coverage

Quality Assurance

Senior Reviewer

Fact-checking and editorial standards compliance