Astronomers at the University of California, Irvine have identified what appears to be the largest stream of super-heated gas ever observed in the universe, flowing out of a nearby galaxy known as VV 340a. The findings were reported in the journal Science.

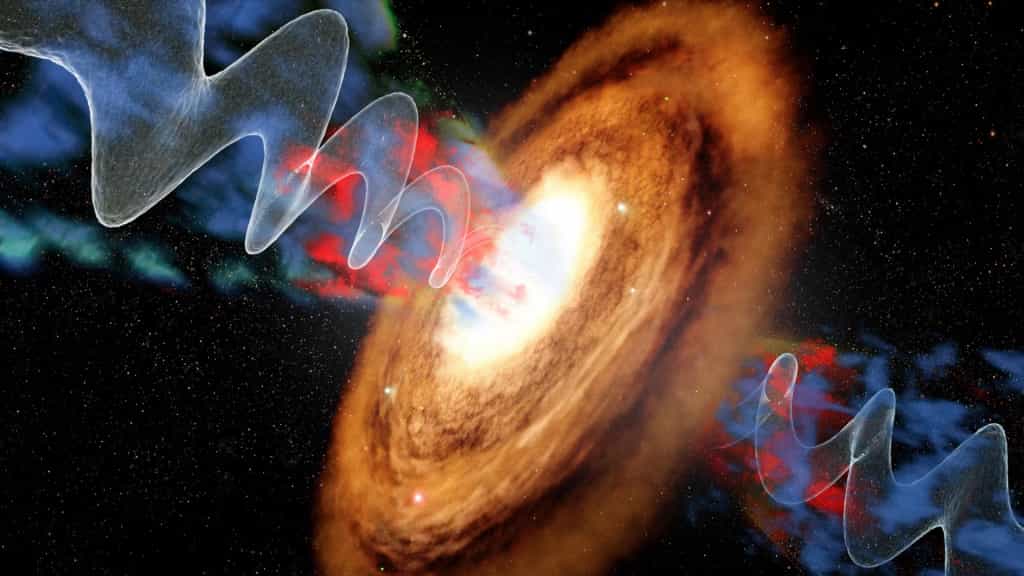

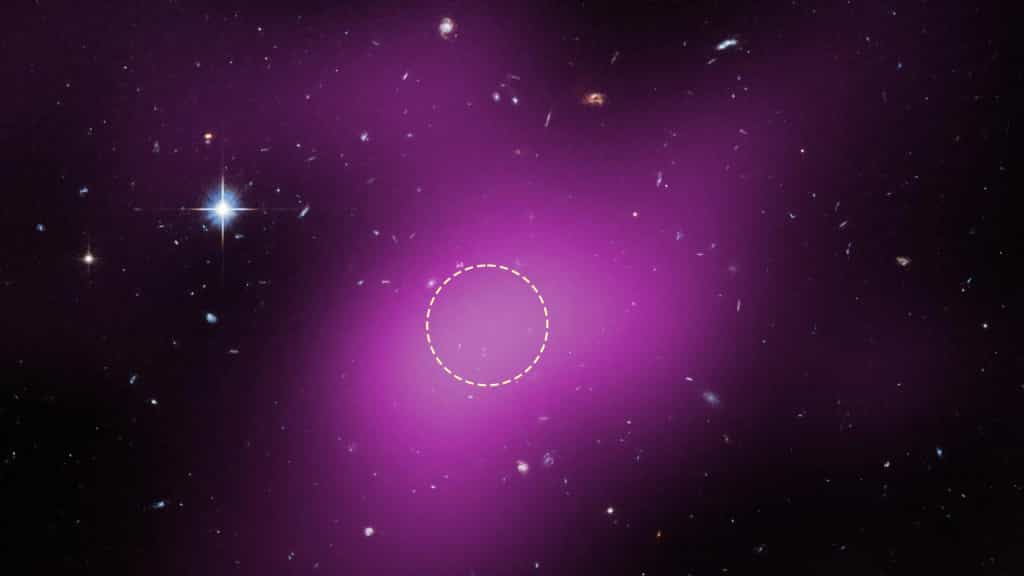

Using data from NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, the researchers detected vast clouds of extremely hot gas erupting from both sides of the galaxy. These glowing structures form two long, narrow nebulae driven by intense activity around a supermassive black hole at the galaxy's core. Each nebula stretches at least three kiloparsecs in length (one parsec equates to roughly 19 trillion miles).

For comparison, the entire disk of the VV 340a galaxy measures only about three kiloparsecs in thickness.

"In other galaxies, this type of highly energized gas is almost always confined to several tens of parsecs from a galaxy's black hole, and our discovery exceeds what is typically seen by a factor of 30 or more," said lead author Justin Kader, a UC Irvine postdoctoral researcher in physics and astronomy.

Radio observations from the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array near San Agustin, New Mexico revealed a pair of massive plasma jets emerging from opposite sides of the galaxy. These jets are known to form when gas falling into a supermassive black hole reaches extreme temperatures and interacts with powerful magnetic fields. As a result, energized material is launched outward at tremendous speeds.

On even larger scales, the jets trace a spiral-like path through space. This pattern points to a process known as "jet precession," which refers to a gradual shift in the direction of the jets over time, similar to the slow wobble of a spinning top.

"This is the first observation of a precessing kiloparsec-scale radio jet in a disk galaxy," said Kader. "To our knowledge, this is the first time we have seen a kiloparsec, or galactic-scale, precessing radio jet driving a massive coronal gas outflow."

As the jets push outward, the team believes they collide with surrounding material inside the galaxy, forcing it away from the center and heating it to extreme temperatures. This process creates what scientists call coronal line gas, a name borrowed from the sun's outer atmosphere to describe highly ionized, super-hot plasma.

According to Kader, this type of coronal gas is usually found very close to a black hole and rarely spreads far into the host galaxy. It is almost never detected outside the galaxy itself, making the new observations highly unusual.

The sheer power of the outflow is staggering. Kader said the energy carried by the coronal gas is equivalent to 10 quintillion hydrogen bombs exploding every second.

"We found the most extended and coherent coronal gas structure to date," said senior co-author Vivian U, a former UC Irvine research astronomer who is now an associate scientist at Caltech's Infrared Processing and Analysis Center. "We expected JWST to open up the wavelength window where these tools for probing active supermassive black holes would be available to us, but we had not expected to see such highly collimated and extended emission in the first object we looked at. It was a nice surprise."

The full picture of the jets and the glowing coronal gas emerged only after the researchers combined data from several observatories. Observations from the University of California-operated Keck II Telescope in Hawaii uncovered cooler gas extending much farther from the galaxy, reaching distances of up to 15 kiloparsecs from the black hole.

The scientists think this cooler material represents a "fossil record" of earlier jet activity. It likely consists of leftover debris from previous episodes when the black hole expelled gas from the galaxy's core.

The coronal gas itself was detected by the Webb telescope, which orbits the sun about one million miles from Earth. As the largest space telescope ever built, Webb observes the universe in infrared light, allowing it to see objects hidden from traditional visible-light telescopes.

This capability was critical for studying VV 340a. The galaxy contains large amounts of dust that block visible light, preventing telescopes like Keck from seeing deep into its interior. Infrared light, however, passes through the dust, making the erupting coronal gas clearly visible in Webb's images.

The impact of the black hole jets on the galaxy is dramatic. According to the study, VV 340a is losing enough gas each year to form 19 stars like our sun.

"What it really is doing is significantly limiting the process of star formation in the galaxy by heating and removing star-forming gas," said Kader.

Clues to the Milky Way's Past and Future

No similar jet appears to be active in the Milky Way today. However, Kader noted that evidence suggests our own supermassive black hole experienced a feeding event about two million years ago, something he said early human ancestors such as Homo erectus may have witnessed in the night sky.

With the discovery of this rare precessing jet and its massive gas outflow, the researchers now plan to examine other galaxies for similar features. Their goal is to better understand how powerful black hole activity can influence the long-term evolution of galaxies like the Milky Way.

"We are excited to continue exploring such never-before-seen phenomena at different physical scales of galaxies using observations from these state-of-the-art tools, and we can't wait to see what else we will find," U said.

Funding for the research was provided by NASA and the National Science Foundation.

Editorial Context & Insight

Original analysis & verification

Methodology

This article includes original analysis and synthesis from our editorial team, cross-referenced with primary sources to ensure depth and accuracy.

Primary Source

All Top News -- ScienceDaily