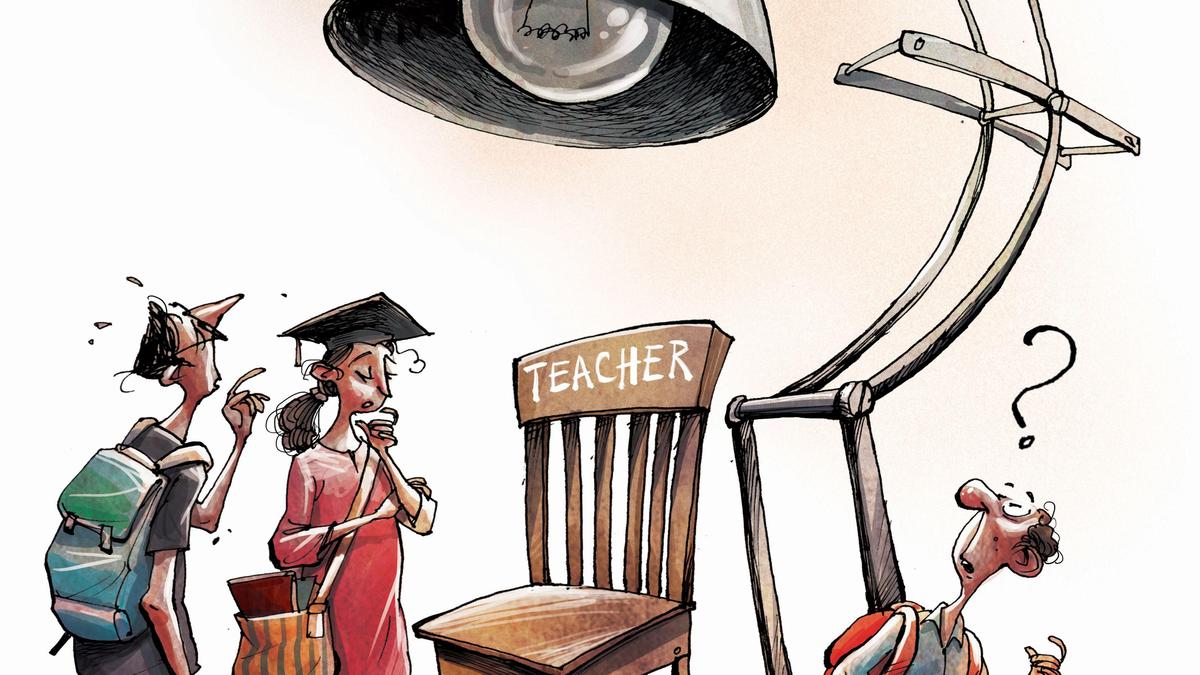

These are disconcerting times for higher education in Tamil Nadu. To begin with, 12 universities in the State have no Vice-Chancellors. Besides the iconic University of Madras, the list of “headless institutions” includes Periyar University, Anna University, Bharathiar University, Madurai Kamaraj University, Bharathidasan University, Tamil Nadu Teachers Education University, Annamalai University, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Tamil Nadu Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Tamil University, and Tamil Nadu Physical Education and Sports University.

Several of them have been functioning without a V-C for at least two years, depriving them of not just administrative leadership but also representation in the higher echelons of the Education Ministry. Over the past two to three years, the regular process of the Governor, in his capacity as the Chancellor, selecting a V-C from among three possible candidates recommended by a search committee has ended in a deadlock.

Governor R.N. Ravi has insisted that the 2018 regulation of the University Grants Commission (UGC) be followed in the appointment of the V-Cs, especially the clause that one member of the search committee must be a UGC nominee. However, the State government has said that since it has not adopted that particular UGC clause, it does not apply it. Tamil Nadu would prefer the process to be guided by State legislation and not Central rules. The resulting impasse has affected the normal functioning of the 12 institutions.

At Bharathidasan University, 10 months have passed since the last V-C, M. Selvam, demitted office, and the delay in appointing a new V-C has raised concern in academic circles. Mr. Selvam, who was the V-C for four years following a one-year extension, left office on February 5. A three-member Vice-Chancellor Convenor Committee was subsequently constituted to perform the duties of the V-C until an appointment was made to the post.

According to university sources, the daily work of the university has slowed down owing to the absence of a V-C. Many decisions are kept pending and some issues only get delayed concurrence because the committee members are in different locations, senior officials said.

The university, which has 38 departments and about 153 affiliated colleges, has been caught in a stalemate over the renewal of its National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) certificate and its annual convocation has been delayed. “When a regular V-C is on the campus, the files and matters of the university will go on without delay, rather than being sent to higher officials for sanction. Though video-conference meetings are held, crucial matters are getting delayed. The physical presence of the V-C is essential for the betterment of the administration,” said David Livingstone, State president of Tamil Nadu Government Collegiate Teachers’ Association.

The absence of a V-C at Madurai Kamaraj University for over a year has badly affected the reputation of the decades-old institution, said a senior professor. “Once MKU produced some of the world-class research papers and studies, but now the poor administration and the State’s tug-of-war with the Governor [Chancellor] have pushed every other thing to the back seat,” he said.

At Periyar University in Salem, the V-C’s post has remained vacant since May. From 2018, the posts of Registrar, Controller of Examination (CoE), and Director of Distance Education remain vacant. In the past seven years, the university administration invited applications for these posts four times.

Filling of the key posts of Registrar and CoE in recent months after years has been welcomed at Bharathiar University in Coimbatore. Yet, in the absence of a full-time V-C, important files continue to be sent to the Secretary of Higher Education, who is the Convenor of the Vice-Chancellor Search Committee, for approval.

“There can never be any quick-fix solution to issues related to teaching, research and extension activities at Bharathiar University without the appointment of a full-time V-C,” said T. Veeramani, former Principal of the Government College for Women, Coimbatore, who had earlier served as the State president of Tamil Nadu Government Collegiate Teachers’ Association.

There are reportedly at least 9,000 vacancies at government colleges across Tamil Nadu. “Around 96 colleges do not have Principals. Without new appointments, staff members who have served for 10 to 20 years are unable to progress to senior positions. They are not eligible for promotion once they reach the age of superannuation,” Mr. Livingstone said.

In May, government arts and science colleges were inaugurated in 15 districts. However, sources said most of them are functioning without proper infrastructure and staff. On October 15, an announcement was made for recruitment of 2,708 assistant professors through the Teachers Recruitment Board (TRB). However, the online application procedure was mired in technical glitches. The Tamil Nadu All Government College UGC Qualified Guest Lecturers Association recently said that over 400 candidates were unable to register for the vacancies, though they had appeared for the TRB examination held in 2024. The association also claimed that colleges where they had worked previously were compounding the problem by delaying the issuance of service/experience certificates by 10-20 days, and some were demanding a fee of ₹2,000-₹10,000 from applicants.

Earlier this year, the body appealed to the Department of Higher Education to transfer guest lecturers, who have been replaced by permanent staff members, to fill the vacancies in other institutions, instead of leaving them in limbo. The affected guest lecturers had served between five and eight years and earned a monthly salary of just ₹25,000. A total of 7,360 guest lecturers are working at 164 government arts and science colleges across Tamil Nadu. In contrast to full-time appointees, guest lecturers earn only 11 months’ salary, without service benefits.

Requesting anonymity, a former V-C said universities that are indeed short of manpower have the leverage to exercise autonomy and revamp the courses for stepping up enrolment of students by offering interdisciplinary programmes. “It makes no sense for the teachers to continue with specialised courses in single-faculty departments and a handful of students. The ideal approach will be to club such departments and offer interdisciplinary programmes suiting the market needs.”

Be it Bharathiar University or the government colleges, the dependence on guest faculty members has been on the rise. But for a few government arts and science colleges of long standing, the guest lecturers far outnumber the regular faculty members. “The government, while sanctioning new programmes, ought to simultaneously issue orders for appointment of regular faculty members. College heads are struggling to optimise the existing manpower for ensuring the stipulated teaching-learning days in an academic year,” a senior faculty member of a government college in Coimbatore district said.

Teachers of government-aided colleges across Tamil Nadu have been demanding the immediate release of revised salaries under the Career Advancement Scheme (CAS) that has been pending for years. A Government Order was issued in 2021 stating that monetary benefits under the CAS would be paid to the teachers of aided colleges from 2018 onwards, though the revision recommended by the Seventh Pay Commission came into effect in 2016.

As things stand, pay fixation has been done for barely 300 teachers in Thanjavur and a few others in Coimbatore and Tiruchi in March 2024, said J. Gandhiraj, president, Association of University Teachers (AUT). “In the past four years, we have approached at least six Higher Education Secretaries and two Ministers. All we ever got were ‘assurances’,” he maintained. There are at least 4,000 teachers at the 163 government-aided colleges across the State who are eligible for the CAS, he pointed out.

Off the record, government officials said the State government was weighed down by a huge loan burden, Professor Gandhiraj added. “In the past six months, they have even stopped issuing CAS orders. We are helpless.”

The AUT and Madurai Kamaraj, Manonmaniam Sundaranar, Mother Teresa, and Alagappa Universities Teachers’ Association (MUTA) have staged at least 40 protests, including a day-long fast at the Directorate of Collegiate Education.

For the past 10 years, there has been no direct recruitment at Tamil Nadu’s government and aided colleges. “The State is just managing by redeployment and ad-hoc staff appointments. A Ph.D. holder who has cleared all exams and does a regular teaching job will get only ₹25,000. There is yet another category of teachers that works for ₹10,000 or ₹8,000. Bureaucratic arrogance is hampering the career of many teachers,” said P.B. Prince Gajendra Babu, general secretary, State Platform for Common School System-Tamil Nadu (SPCSS-TN).

Added to this is the administrative bookkeeping generated by the introduction of initiatives such as Naan Mudalvan, Pudhumai Penn, and Tamil Pudhalvan. “Though these programmes are an excellent opportunity for young people, especially rural students, the government should have also planned for a separate entity to coordinate the data collection required for these schemes. As of now, whether it is student orientation or data collection for uploading on the system, it is all being done by teachers. This affects their routine classwork, and many teachers are doing the work of upper division clerks,” said Mr. Livingstone.

Interestingly, Tamil Nadu topped the 2024 National Institutional Ranking Framework (NIRF) Rankings, with 18 institutions in the Top 100 Overall Rankings. “The State has a rich history of educational institutions and continues to thrive in the field of higher education. With an ever-expanding infrastructure, rigorous academic programmes, and a commitment to improving quality standards, Tamil Nadu has established itself as the leading State in the country for higher learning with an astounding Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER),” according to the Policy Note for 2025-26 issued by the Higher Education Department.

This has created a chasm between the ground reality and idealistic standards promoted by policymakers at the State and Central levels. Several educationists also see a move to replace the existing system with the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020. “Tamil Nadu is known for social justice, where all sections of society can access higher education. It is sad to see its educational set-up being systematically demolished,” said Mr. Babu. “When the Centre implements the NEP 2020, without the concurrence of States, it wants to ensure that the present system of universities collapses.”

The Higher Education Commission of India Bill, 2025, (Viksit Bharat Shiksha Adhishthan Bill, 2025) could increase the role of the Central government in the sector, feel academics. “This is not an ordinary Bill in Parliament. It will sabotage the entire system and allow foreign players in the field, affecting vulnerable sections of students. The main goal of the NEP 2020 is to promote privatisation and commercialisation of education,” said Mr. Babu.

In essence, Tamil Nadu’s educational framework is being weakened, and this is an issue that will have a ripple effect on the coming generation of students.

(With inputs from Saptarshi Bhattacharya in Chennai, R. Krishnamoorthy in Coimbatore, C. Palanivel Rajan in Madurai, and M. Sabari in Salem)