At 74, Vidya Devi Soni’s passion for Mandana, a traditional Indian folk art form, opens a window into a world of hand-drawn artwork, rooted in tradition and memory. As the Mandana artist traces her journey from novice to seasoned artist, she grows nostalgic about an art form that once adorned nearly every lane of her hometown, Bhilwara, in Rajasthan, and is now struggling to survive in an era threatened by anonymity and fading traditions.

Predominantly made on the floors of kuchcha (temporary) houses, Mandana is a distinctive mark of identity for many, like Vidya. However, these designs are losing their relevance amid the prevalence of pucca (permanent) houses and ready-made stickers. “It is best represented on mud floors. Designs made in a white-red combination perfectly pop out on a floor smeared with a mixture of soil and cow dung,” Vidya tells indianexpress.com.

For most people, it is just another colourful pattern on the floor—something vaguely familiar, often confused with rangoli, admired for a moment and then forgotten. But for Vidya, it’s her entire childhood. “I grew up making it,” she reflects.

Mandana carries centuries of ritual, symbolism, and lived memory within its simple red-and-white lines. Today, as concrete replaces mud floors and ‘readymade’ alternatives overtake tradition, this gradually vanishing art form is being kept alive by a handful of families, like the Soni family, who remember what it truly meant.

“People like it, they admire it, but they don’t really understand it. They don’t know why it was made, on which occasion, or what each design symbolised,” says Vidya.

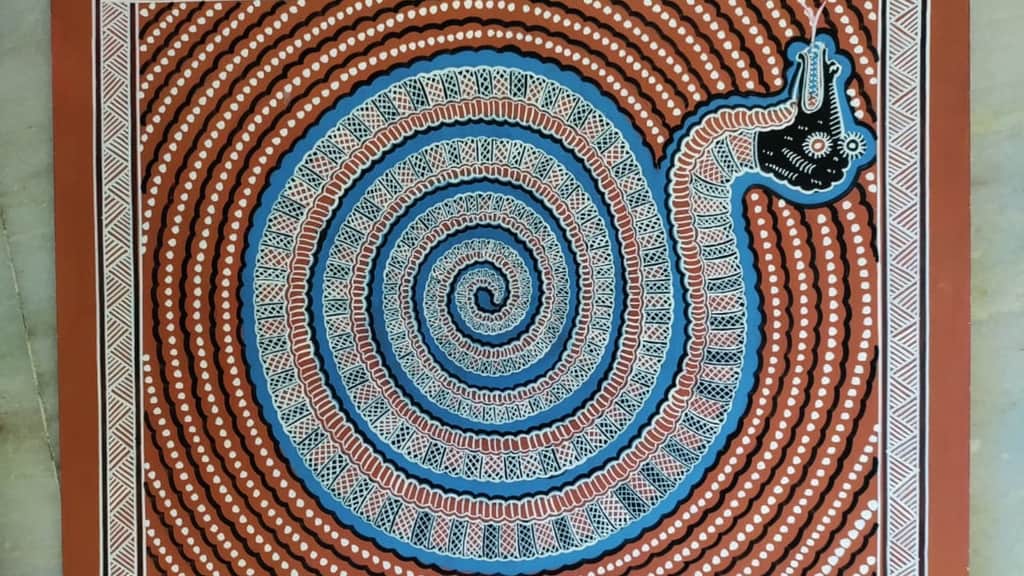

Mandana by Vidya Devi Soni (Photo: Dinesh Soni)

Mandana was never merely decorative. Traditionally made on freshly plastered mud floors using natural pigments, it marked life itself—festivals, seasons, marriages, childbirth, and transitions within a household. When a daughter left for her maternal home, when a bride entered a new house, when Diwali arrived, or when the seasons changed, Mandana appeared on the floor as a quiet yet powerful expression of belief and continuity.

The art was passed down organically. “I learned it from my mother,” Vidya recalls. “In those days, every house made Mandana. It was part of daily life.”

But it isn’t as simple as it seems, emphasises Vidya. “Mandana follows a strict vocabulary. Each motif has a name and a purpose—such as chariots, birds, cow motifs, lamps, and seasonal symbols—created in accordance with festivals and rituals. Diwali, for instance, had its own Mandana patterns centred around lamps and prosperity.”

Over time, Mandana has increasingly been mistaken for rangoli, a more contemporary and decorative form of floor art. However, Vidya insists that the difference is fundamental.

“Mandana is made directly on the floor of the home—traditionally a mud floor first plastered with cow dung and clay. The colours are limited and natural: geru, a red-brown earth pigment, and khadiya, a white chalky clay. Both are sourced from the earth, ground by hand, and applied with precision,” she explains.

Rangoli, on the other hand, uses commercially produced powders, often brightly coloured and mixed freely. “Rangoli today is mostly about decoration,” elaborates Vidya. “The computer-generated designs, stencils, and readymade powders don’t have depth. There is no symbolism, no ritual meaning. It is just plain visual beauty lacking any meaning.”

Mandana, by contrast, is a form of ritual art. “Every line has intent,” reiterates the septuagenarian.

Mandana artist Vidya Devi Soni (Photo: Dinesh Soni)

The decline of Mandana began quietly, with the disappearance of mud houses. As villages shifted to concrete homes, the rough, absorbent floors that once held Mandana for weeks were replaced by smooth surfaces that wiped clean in a day.

“On mud floors, Mandana would merge with the surface and stay for months,” says Vidya. “Concrete floors are swept and washed daily. The art vanishes almost immediately,” she adds.

Faced with this reality, Vidya made a crucial decision: adapt the medium, not the method. To ensure survival, Mandana was shifted from floors to cotton cloth and hard sheets, retaining the same pigments, techniques, and symbolism. These works are now used as wall art—allowing urban homes to engage with the tradition without altering its essence.

“The art form is the same,” she insists. “Only the surface has changed.”

Vidya’s son, Dinesh Soni, a Pichwai Chitrakar by profession, has been resiliently working to preserve the art form. “People from across the country want to learn the art,” he reveals, adding that sometimes, people from cities as far away as Mumbai, Surat, and Delhi also travel to Bhilwara to learn Mandana.

Age groups vary widely, says Dinesh. “Young Gen Z learners are also drawn by a desire to reconnect with something rooted and meaningful,” he adds.

Yet challenges remain. Online teaching is challenging for an art form that relies so heavily on physical demonstration, texture, and material. “People want to learn online, but Mandana doesn’t translate easily to a screen,” he admits.

Vidya Devi Soni making ‘Mandana’ on floor (Photo: Dinesh Soni)

Despite its cultural significance, Mandana remains largely unrecognised at the institutional level. “Efforts were made to classify it as an endangered art form, surveys were conducted, and even parliamentary questions were reportedly raised. Yet, years later, no formal protection or sustained government support has materialised,” shares Dinesh.

“There was a survey, there were discussions—but nothing concrete came out of it,” he adds. “If this continues, many such arts will simply vanish.”

Mandana is not tied to a single community or caste. “It once belonged to everyone. Every household knew it, just as every woman knew how to apply mehendi. That universality is perhaps what makes its loss so profound,” shares Vidya.

In Rajasthan, where cultural continuity remained relatively stable compared to other regions, Mandana survived longer. Elsewhere, migration and disruption altered forms and meanings to the point of being unrecognisable.

Today, what remains is fragile—but not extinct.

“We don’t just want to preserve it,” says Vidya. “We want it to travel. We want young people to learn it, earn from it, innovate with it—without losing its soul,” she adds.

Editorial Context & Insight

Original analysis & verification

Methodology

This article includes original analysis and synthesis from our editorial team, cross-referenced with primary sources to ensure depth and accuracy.

Primary Source

The Indian Express