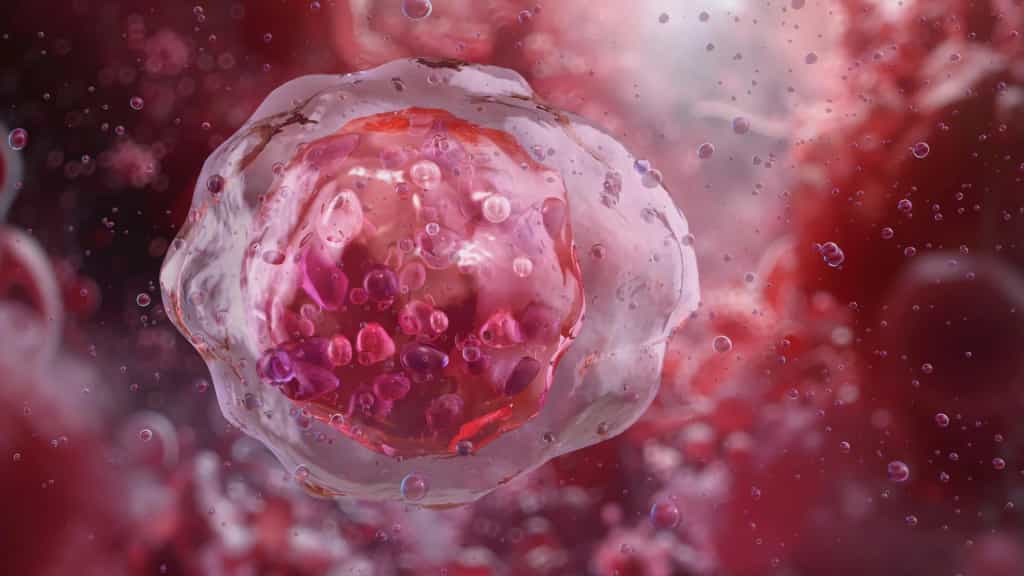

A new artificial intelligence system that examines the shape and structure of blood cells could significantly improve how diseases such as leukemia are diagnosed. Researchers say the tool can identify abnormal cells with greater accuracy and consistency than human specialists, potentially reducing missed or uncertain diagnoses.

The system, known as CytoDiffusion, relies on generative AI, the same type of technology used in image generators such as DALL-E, to analyze blood cell appearance in detail. Rather than focusing only on obvious patterns, it studies subtle variations in how cells look under a microscope.

Many existing medical AI tools are trained to sort images into predefined categories. In contrast, the team behind CytoDiffusion demonstrated that their approach can recognize the full range of normal blood cell appearances and reliably flag rare or unusual cells that may signal disease. The work was led by researchers from the University of Cambridge, University College London, and Queen Mary University of London, and the findings were published in Nature Machine Intelligence.

Identifying small differences in blood cell size, shape, and structure is central to diagnosing many blood disorders. However, learning to do this well can take years of experience, and even highly trained doctors may disagree when reviewing complex cases.

"We've all got many different types of blood cells that have different properties and different roles within our body," said Simon Deltadahl from Cambridge's Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, the study's first author. "White blood cells specialize in fighting infection, for example. But knowing what an unusual or diseased blood cell looks like under a microscope is an important part of diagnosing many diseases."

A standard blood smear can contain thousands of individual cells, far more than a person can realistically examine one by one. "Humans can't look at all the cells in a smear -- it's just not possible," Deltadahl said. "Our model can automate that process, triage the routine cases, and highlight anything unusual for human review."

This challenge is familiar to clinicians. "The clinical challenge I faced as a junior hematology doctor was that after a day of work, I would face a lot of blood films to analyze," said co-senior author Dr. Suthesh Sivapalaratnam from Queen Mary University of London. "As I was analyzing them in the late hours, I became convinced AI would do a better job than me."

To build CytoDiffusion, the researchers trained it on more than half a million blood smear images collected at Addenbrooke's Hospital in Cambridge. The dataset, described as the largest of its kind, includes common blood cell types, rare examples, and features that often confuse automated systems.

Instead of simply learning how to separate cells into fixed categories, the AI models the entire range of how blood cells can appear. This makes it more resilient to differences between hospitals, microscopes, and staining techniques, while also improving its ability to detect rare or abnormal cells.

When tested, CytoDiffusion identified abnormal cells associated with leukemia with much higher sensitivity than existing systems. It also performed as well as or better than current leading models, even when trained with far fewer examples, and was able to quantify how confident it was in its own predictions.

"When we tested its accuracy, the system was slightly better than humans," said Deltadahl. "But where it really stood out was in knowing when it was uncertain. Our model would never say it was certain and then be wrong, but that is something that humans sometimes do."

Co-senior author Professor Michael Roberts from Cambridge's Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics said the system was evaluated against real-world challenges faced by medical AI. "We evaluated our method against many of the challenges seen in real-world AI, such as never-before-seen images, images captured by different machines and the degree of uncertainty in the labels," he said. "This framework gives a multi-faceted view of model performance which we believe will be beneficial to researchers."

The team also found that CytoDiffusion can generate synthetic images of blood cells that look indistinguishable from real ones. In a 'Turing test' involving ten experienced hematologists, the specialists were no better than random chance at telling real images apart from those created by the AI.

"That really surprised me," Deltadahl said. "These are people who stare at blood cells all day, and even they couldn't tell."

As part of the project, the researchers are releasing what they describe as the world's largest publicly available collection of peripheral blood smear images, totaling more than half a million samples.

"By making this resource open, we hope to empower researchers worldwide to build and test new AI models, democratize access to high-quality medical data, and ultimately contribute to better patient care," Deltadahl said.

Supporting, Not Replacing, Clinicians

Despite the strong results, the researchers emphasize that CytoDiffusion is not intended to replace trained doctors. Instead, it is designed to assist clinicians by quickly flagging concerning cases and automatically processing routine samples.

"The true value of healthcare AI lies not in approximating human expertise at lower cost, but in enabling greater diagnostic, prognostic, and prescriptive power than either experts or simple statistical models can achieve," said co-senior author Professor Parashkev Nachev from UCL. "Our work suggests that generative AI will be central to this mission, transforming not only the fidelity of clinical support systems but their insight into the limits of their own knowledge. This 'metacognitive' awareness -- knowing what one does not know -- is critical to clinical decision-making, and here we show machines may be better at it than we are."

The team notes that additional research is needed to increase the system's speed and to validate its performance across more diverse patient populations to ensure accuracy and fairness.

The research received support from the Trinity Challenge, Wellcome, the British Heart Foundation, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust, Barts Health NHS Trust, the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, NIHR UCLH Biomedical Research Centre, and NHS Blood and Transplant. The work was carried out by the Imaging working group within the BloodCounts! consortium, which aims to improve blood diagnostics worldwide using AI. Simon Deltadahl is a Member of Lucy Cavendish College, Cambridge.

Editorial Context & Insight

Original analysis and synthesis with multi-source verification

Methodology

This article includes original analysis and synthesis from our editorial team, cross-referenced with multiple primary sources to ensure depth, accuracy, and balanced perspective. All claims are fact-checked and verified before publication.

Primary Source

Verified Source

All Top News -- ScienceDaily

Editorial Team

Senior Editor

Dr. Amara Okafor

Specializes in Science coverage

Quality Assurance

Associate Editor

Fact-checking and editorial standards compliance