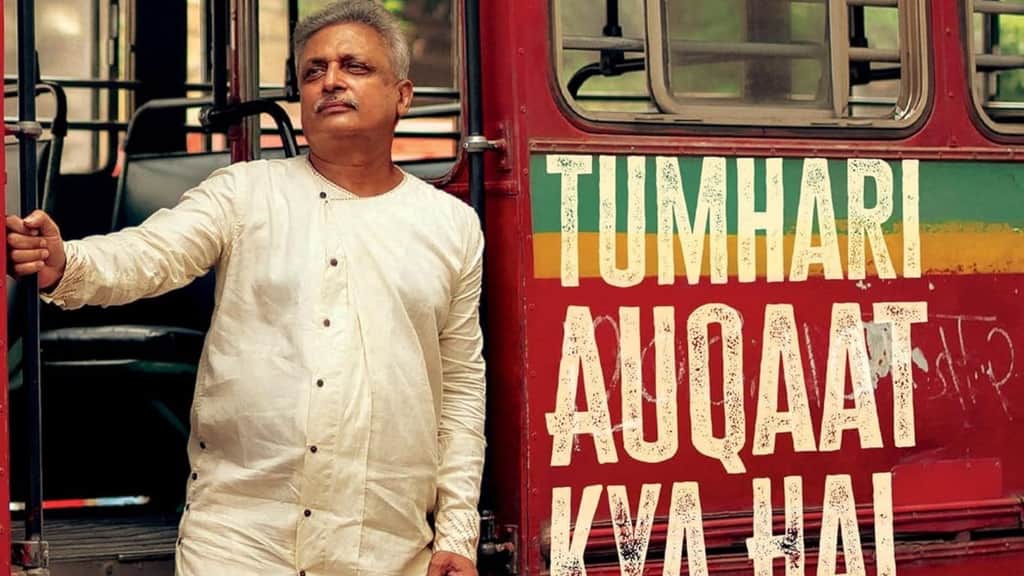

Piyush Mishra has spent decades being celebrated as a voice of artistic integrity, but his novelised memoir, Tumhari Auqaat Kya Hai, Piyush Mishra, is not interested in celebration.

Written against the grain of autobiography, the book dismantles the mythology that has grown around him and replaces it with a quieter, more unsettling inquiry into worth, failure, and survival and by the time he asks, “Tumhari auqaat kya hai?”, the question no longer feels rhetorical.

It is addressed not just to the reader, but to the man who has spent four decades slipping between identities.

For readers who recognise the name but not the range, Mishra is a study in multiplicity. He is a poet who sings, an actor who writes, a musician who performs with unguarded intensity, and now a novelist.

But again for a person whose work is a symbol of a dissenter, and a devotee of disorder, the autobiography arrives disguised as fiction, its author fragmented into alter egos such as Santap Trivedi, Haider, and Hamlet, each a shard of the same restless self. Names change. Cities recur. Truth remains intact.

What emerges is a book that behaves less like a linear life story and more like a long theatrical monologue, one that circles memory, contradiction, and regret with deliberate crookedness. “Thoda tedha novel hai, par ekdum seedha bhi hai,” Mishra says. It is a crooked novel, but also a very straight one.

In Tumhari Auqaat Kya Hai, Piyush Mishra, a story resounding with dark humour and lyrical rage, he holds nothing back. (Source: HarperCollins India)

At its heart, the book is shaped by cities. Gwalior, Delhi, and Mumbai are not passive settings. They act, instruct, and demand. Together, they form the architecture of Mishra’s becoming.

Gwalior, where Mishra grew up, appears as a place of latent inheritance. A city steeped in Hindustani classical music and the birthplace of Tansen, it offered him something ineffable but incomplete. “In Gwalior, I first learnt that I am capable of doing this,” he says. “But I didn’t know what to do with it or where it came from.” Talent existed there in fragments, song, acting, instinct, without a language to assemble them.

Delhi, by contrast, was instruction. For nearly two decades, Mishra lived there in near permanent scarcity, surviving on theatre and conviction. “Delhi strictly taught me how to gather everything,” he recalls, music, writing, performance, structure. It was here that confusion gave way to discipline. “Before that, I didn’t know whether I was a writer, musician, singer, or actor. Delhi showed me the line.”

The clarity came at a cost. There was no money, only work. “I did everything in disturbance,” he says. Yet Delhi also gave him something more durable than comfort. It taught him how to be serious about art, even when art offered nothing in return.

Mumbai is liberation and compromise. It is the city that paid him. “I got money, real money, for the first time in my life,” Mishra says. “Money gives you mental peace. It liberates you to work.” Fame followed, along with the inevitability of change. Flyovers replaced corners. Speed replaced solitude.

Mumbai gave Mishra a band, poetry collections, cinema, and now this book. It also demanded acceptance. “You can’t challenge change,” he says. “Even I have to accept it.” The city did not shape his art as much as it stabilised the conditions under which art could survive.

What distinguishes Mishra’s memoir from the glut of celebrity life writing is its refusal to mythologise struggle. He writes openly about alcoholism, failure, and being far from the man audiences now revere. “A generation started looking at me as a god,” he says. “If they knew what I was like in the ’80s or ’90s, my image would be ruined.”

The solution was not confession in the traditional sense, but distance. Mishra adopts a bird’s eye view. “When you look from too close, the pain can be too much,” he explains. Early drafts written entirely in the first person were discarded. They felt dishonest in their self absorption. Fiction, paradoxically, allowed for greater honesty. “I enjoy saying things in a crooked way,” he admits. “It’s my temperament.”

Also, as per Mishra, the book’s structure was not planned, it emerged. “Writing is never done with deliberate thought,” Mishra says. “It’s intuition.”

He describes the novel as a performance unfolding in his mind, images running continuously like a screenplay until the pen could no longer keep up. Hence, what we read describes efficiently that theatre remains his moral anchor. In his Delhi years, he studied not just plays but sculptors, architects, and writers. Art, for Mishra, is accumulative rather than singular. Each discipline feeds the other. Nothing exists in isolation.

The title of the book functions as its ethical centre. Auqaat, worth, standing, capacity, is not framed as social hierarchy but as moral accounting. “At night, when we sleep, we are naked before our own decisions,” Mishra says. “Everything is visible.”

“We commit so many misdeeds in life that by the end, we have a bundle of sins. We should all ask what our worth (aukaat) is. At night, before sleeping, you see what you did all day, how many bad deeds you committed. It should be asked, and those who can accept it, tell it.”

He speaks of apologising where he was wrong and forgiving where he was hurt. “I think about myself that where I have done something wrong, I have apologised. I have related it too. If I did bad deeds, I rejected them and said sorry. And where people did things to me, I forgave them. Both things are beneficial.,” he says. “One taught me to ask for forgiveness, and the other taught me to forgive.”

And with to that Mishra gives no grand conclusions, what he offers instead is exposure. “I laid everything bare,” Mishra says. Judgment is left to the reader. That readers have responded with acceptance rather than rejection seems to have surprised even him. “It means people can drink the truth.”

In an age of carefully managed personas and algorithm friendly vulnerability, this book feels quietly defiant. It resists branding, refuses linearity, and mistrusts reverence. Mishra does not ask to be admired. He asks to be read and, perhaps, to be questioned.

By the end, the question lingers, uncomfortably transferable. Mishra has answered for himself. The rest is up to us.

Editorial Context & Insight

Original analysis & verification

Methodology

This article includes original analysis and synthesis from our editorial team, cross-referenced with primary sources to ensure depth and accuracy.

Primary Source

The Indian Express