The Election Commission on Tuesday told the Supreme Court that it functions as the original authority in matters relating to electoral rolls and conduct of polls and its opinion is binding on the President if a person acquires citizenship of another country.

The panel submitted that the consequence of an adverse finding during the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) would only be exclusion of the person's name from the electoral roll and does "not ipso facto (by that very fact) result in deportation”, but it may be referred to the Centre for scrutiny and possible action under the Citizenship Act and related laws.

It also pointed out that in several regulatory frameworks, such as those governing mining leases or other statutory benefits, citizenship is a prerequisite and can be inquired into by the competent authority, countering the argument that the poll panel was exceeding its constitutional mandate.

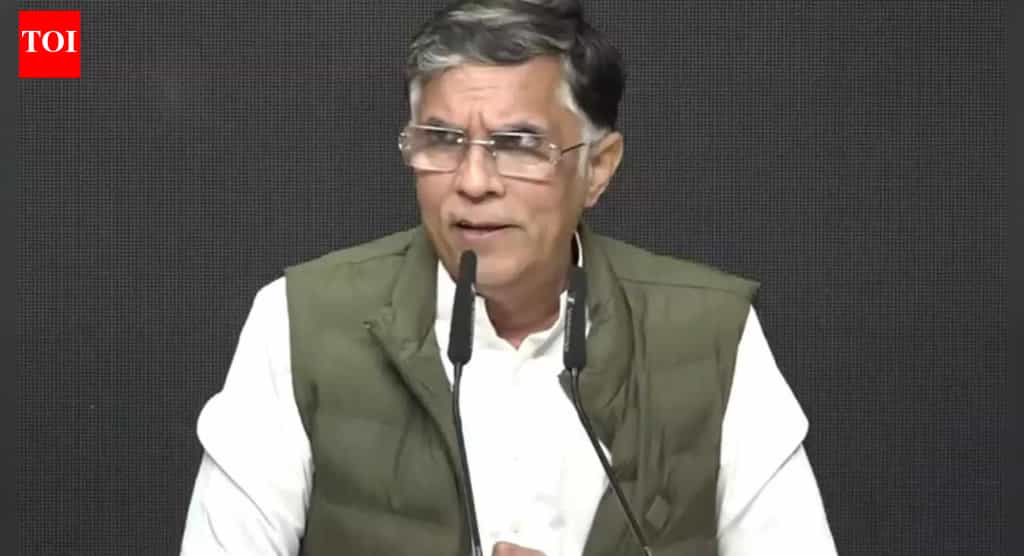

The submissions were made by senior advocate Rakesh Dwivedi on behalf of the EC before a bench of Chief Justice Surya Kant and Justice Joymalya Bagchi which resumed final hearings on a batch of petitions that challenged the EC's decision to undertake the SIR exercise in several states, including Bihar, raising significant constitutional questions on the scope of the poll panel's powers, citizenship and the right to vote.

The bench heard extensive submissions from Dwivedi, who defended the SIR exercise as being squarely within the constitutional and statutory mandate of the poll body and rejected the contention that it was a parallel citizenship-determination process similar to the National Register of Citizens (NRC).

He submitted that the Electoral Registration Officer (ERO), acting under the EC’s supervision, is competent to conduct a limited inquisitorial inquiry for electoral purposes.

Dwivedi said in matters relating to elections, electoral rolls and the conduct of polls, the poll panel functions as the de facto (in reality) authority.

Referring to Section 146 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, particularly Sections 146A to 146C, the senior lawyer submitted that Parliament has provided a detailed statutory mechanism empowering the EC to conduct hearings, take decisions and even exercise powers akin to those of a civil court for deciding questions relevant to electoral rolls.

“If a person acquires, or is alleged to have acquired, the citizenship of another country, it is ultimately the Election Commission which examines the issue for electoral purposes, and its opinion is binding on the President,” Dwivedi told the court, emphasising that such scrutiny is limited to determining eligibility for inclusion in the voter list.

He clarified that the consequence of an adverse finding during the SIR would only be exclusion of the person’s name from the electoral roll.

“It does not ipso facto result in deportation,” Dwivedi said, adding that in appropriate cases, the matter may be referred to the central government for scrutiny and possible action under the Citizenship Act, the Foreigners Act and related laws.

Explaining the interplay between different statutes, Dwivedi said that while the Citizenship Act, 1955, governs the acquisition and determination of citizenship, other enactments, including election laws, require authorities to examine citizenship for limited statutory purposes.

He pointed out that in several regulatory frameworks, such as those governing mining leases or other statutory benefits, citizenship is a prerequisite and can be inquired into by the competent authority.

Addressing concerns that the SIR exercise could amount to a parallel citizenship-determination process similar to the National Register of Citizens (NRC), he said, “The electoral roll is fundamentally different from the NRC. The NRC includes all persons, whereas the electoral roll includes only citizens above the age of 18 who are otherwise qualified.”

Persons of unsound mind or otherwise disqualified, he added, cannot be included in the voter list. He said the Constitution itself mandates that only citizens can vote under Article 326, and that the Election Commission has a constitutional duty to ensure that no foreigner is registered as a voter.

“Even if there are 10 or thousands of foreigners on the rolls, they have to be excluded. This is not a political judgment but a constitutional obligation,” he said.

During the hearing, Justice Bagchi observed the evolution of citizenship law, saying, “We have funnelled our citizenship. First, it was birth plus one parent had to be Indian. Now, the birth plus two parents have to be Indians.”

Dwivedi responded by tracing the historical context of citizenship provisions, referring to Article 5 of the Constitution and Constituent Assembly debates of January 1949.

He noted that at the time of independence and the first general elections, India was in a unique and transitional phase.

“The Citizenship Act came only in 1955. Part II of the Constitution on citizenship was yet to be finalised when the Assembly debates were taking place,” he said, adding that judgments and constitutional provisions must be understood in their historical and political context, not as rigid or “mathematical formulas”.

Justice Bagchi, however, queried whether a person’s right to vote could be taken away while a citizenship issue is pending before the central government.

Dwivedi responded that any restriction would be only for the limited purpose of examining eligibility to remain on the electoral roll, and questions relating to stay in India or deportation would fall within the government’s domain. The bench is likely to resume hearing on Thursday.

Editorial Context & Insight

Original analysis and synthesis with multi-source verification

Methodology

This article includes original analysis and synthesis from our editorial team, cross-referenced with multiple primary sources to ensure depth, accuracy, and balanced perspective. All claims are fact-checked and verified before publication.

Primary Source

Verified Source

mint - news

Editorial Team

Senior Editor

Aisha Patel

Specializes in India coverage

Quality Assurance

Associate Editor

Fact-checking and editorial standards compliance