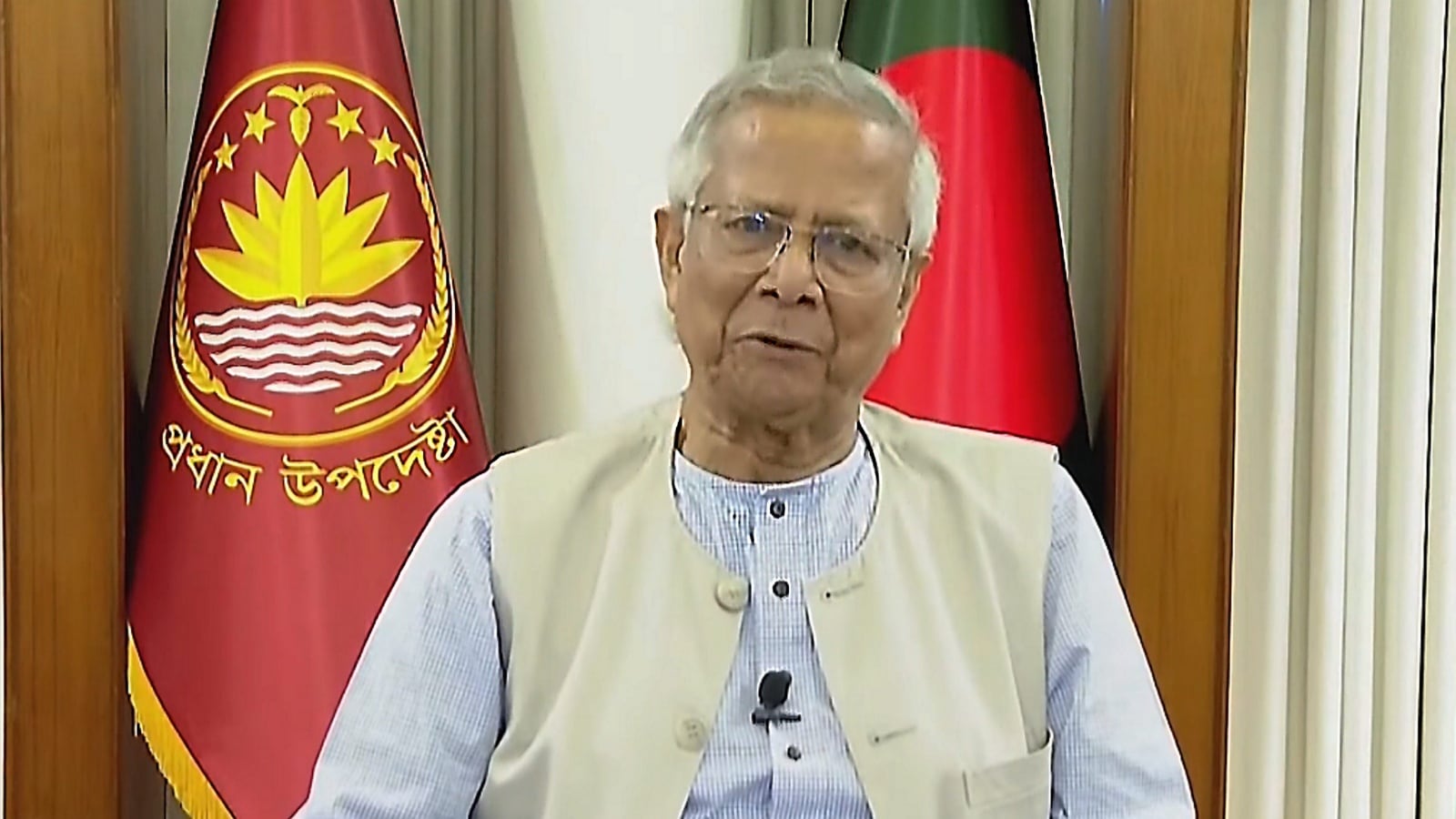

Bangladesh is currently experiencing a noticeable increase in fundamentalism and intolerance. The recent attack on the syncretic cultural institution Chhayanot is not a one-off incident; it is part of a broader campaign targeting symbols of secular and plural culture. All this has happened since Muhammad Yunus and his caretaker government took over the administration.

The swift erosion of India–Bangladesh relations was hardly surprising. India’s support of the Awami League’s authoritarian rule had turned many Bangladeshis against it. Still, New Delhi decided to go out of its way to back the interim government despite its flouting of human rights and democratic principles. In hindsight, this policy has imposed an enormous strategic and moral price.

Much has already been said about the nature of the uprising — celebrated as a spontaneous, leaderless movement inspired by digital natives of a new generation who no longer need the mediation of formal organisations or established political machines. I wonder if we should always believe only the facts displayed. Such a large-scale rebellion would have been impossible to organise without external inducement or support. And the armed forces and police did not decide to play along overnight. To relegate this to a spontaneous flare-up is to miss the geopolitics at play.

In the past few years, it has become clear that Bangladesh is in the process of rewriting its history once more. The country seems to be heading towards religious extremism and majoritarianism. Minorities are vilified and oppressed, militant religious groups are on the rise again, and the secular forces that used to emphasise the linguistic and cultural roots of Bengali identity have fallen into a drastic retreat. Inconceivable though it may have seemed earlier, there now exists an increasingly congenial relationship between Dhaka and Islamabad — the aim is to reimagine the making of Bangladesh itself in ways that can finally lead to a full normalisation of relations with Pakistan.

This transition dovetails nicely with Bangladesh’s growing association with China. Although Dhaka has had strong economic and business connections with Beijing, they are now expanding into defence and strategic partnerships. Significant Chinese investments in infrastructure, ports, and roads are underway, and one hears whispers of a possible link-up among Bangladesh, Pakistan, and China. Callous political voices no longer shy away from threatening India’s strategic and maritime interests in the east, with talk of cutting off India’s northeastern states trending.

India, however, has been measured on these matters till now. Its own treatment of minorities in recent times has undermined whatever moral capital it thought it had in objecting to Bangladesh’s conduct towards its Hindu and Buddhist communities. Still, one is perplexed by New Delhi’s near-collapse in strategic matters. Bangladesh’s increasingly close relationship with both Pakistan and China threatens India’s security in the northeast. Combined with an increase in religious extremism, a new and high-stakes form of anti-Indian politics is growing in Dhaka. India’s tepid objections and knee-jerk reactions only embolden these forces.

The chequered electoral history of Bangladesh, marked by little transparency or fairness, means any future government will also be dependent on fundamentalist forces. You could make the argument that India’s options are hopelessly stunted: It does not have a political formation to support, and its own slide into majoritarianism merely confirms similar proclivities on the other side of the border. But strategic paralysis is not possible. India cannot but act at such a pivotal moment.

New Delhi must formulate a strategy to deter further consolidation among its adversaries. Should diplomacy and economics falter, stronger steps are necessary. Strengthening ties with Myanmar should be an immediate priority, especially given the strained relations between Dhaka and Naypyidaw. At the same time, India must deepen engagement with Southeast Asian states to avoid strategic isolation should a limited conflagration erupt in the eastern theatre. China may press Myanmar to soften its stance towards Bangladesh, making a broader regional outreach all the more necessary.

India also needs to examine the evolving US–Bangladesh relations closely. One cannot dismiss the accounts, regardless of their truthfulness, of Washington’s hidden involvement in the Hasina government’s downfall. Recent strains in Indo–US ties, combined with President Donald Trump’s fondness for Pakistan’s military leadership, further constrain India’s strategic room for manoeuvre.

History casts a long shadow over these developments. Bangladesh was part of Pakistan until 1971. The Partition was founded on religious difference, making Islam an initial pillar of East Pakistan’s identity. Yet the ineluctable conflict between Urdu and Bengali as languages of power and imagination exposed the fragility of religion as a political bond. Bangladesh was ultimately born on the anvil of language. Since then, the nation has oscillated uneasily between these two identities — the secular-linguistic and the religious. The chasm between them has never truly been bridged.

Today, a section of the younger generation, animated by the volatility of global politics, seems eager for a “fresh start”, without fully grasping what such a rupture might entail. Yet, Bangladesh’s independence emerged from a brutal war between India and Pakistan, and from the unprecedented violence unleashed by the Pakistani armed forces in 1971. The nation’s memory holds the genocide, which can’t be erased by history-rewriting zealots.

How Bangladesh comes to terms with its past, present, and future is, of course, its sovereign right. Yet in South Asia, our destinies are deeply intertwined. Ethnic violence spills across borders; majoritarianism in one society excites similar impulses in another. Fundamentalism is not an isolated affliction but part of a wider, organically linked crisis of identity across the subcontinent.

These differences have now acquired visceral intensity. Internal divisions are increasingly securitised; social relations militarised; political ties reduced to strategic exigencies. When such collective madness takes hold, nations lose meaningful choice. Peace becomes a luxury in an age when maximalists wield power.

India must recognise its growing loneliness in a deteriorating strategic environment. Yet, solitude can also invite sober reflection. If unfriendly states are poised to gang up against it, a resolute strategic response becomes imperative. Kid gloves will no longer suffice. If India cannot ensure a friendly dispensation in Bangladesh, it must at least neutralise Bangladesh’s capacity to harm its interests. And it must start acting right away.

The writer teaches at Jadavpur University, Kolkata, and was the Eugenio Lopez Visiting Chair at the Department of International Studies and Political Science at Virginia Military Institute, US