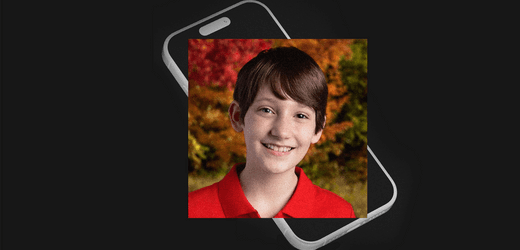

X.com Facebook E-Mail X.com Facebook E-Mail Messenger WhatsApp It is still dark outside when two patrol officers ring Leslie Taylor's doorbell in the morning of January 17, 2022, getting her out of bed. Around 6 a.m. in the suburb of Gig Harbor, near the city of Seattle. "Do you know where Jay is?" the 47-year-old teacher hears one of the two officers ask. She leads the officers to the second floor of the house and opens the door to her 13-year-old son's bedroom. The bed is empty. This story is about extreme violence, sexual harassment and suicide. If you or someone you know is experiencing suicidal thoughts or has been the victim of online harassment or violence, there are many places that can help. Here is a selection: Hotline for suicidal thoughts: In the United States: 988 In the United Kingdom: 0800 587 0800 In Germany: 0800 111 0 111 Help following sexual abuse: In the United States: 1 800 656 4673 In the United Kingdom: 0808 500 2222 In Germany: 0800 2255 530 One of the two officers turns to the father, Colby Taylor, who has now joined them. The officer struggles for words, trying to explain what happened an hour and a half earlier: "We came because of your son," he begins. Before he can finish speaking, Colby Taylor says: "He did it, didn't he?" Jay with his parrot Melon. Foto: Privat The patrol officers only nod, in Leslie and Colby Taylor’s recollection, before then telling them that Jay had been found. He had hanged himself behind a supermarket about a 15-minute walk away. "I never thought I would have to bury my 13-year-old son," says Leslie Taylor. "It was the beginning of an endlessly dark period for us." Leslie and Colby Taylor in the yard of their home in Gig Harbor. Foto: Annabel Clark / The Washington Post "Not a day goes by that I don't miss Jay," says Colby Taylor. "We tried everything to save him, but in the end, there was this dark power from the internet that we didn't know about." After the officers leave on that morning in January 2022, Leslie and Colby Taylor sit in silence on the couch in their living room for a moment. In the corner of the room stands a record player – father and son enjoyed listening to Green Day together. Family photos hang on the walls – hiking trips in the mountains, Jay's birthday weekend with the family on a llama farm, Jay with his two older brothers and his younger brother. But on this Monday morning, Leslie and Colby Taylor have no time to grieve. They must try to stay strong. Soon, their other three sons will wake up and start asking questions for which they don’t yet have any answers. Colby Taylor pops open the couple's silver MacBook, logs out of his work as a manager at a large U.S. tech company, and types into the Google search bar: "How to talk to children when their sibling commits suicide?" At around 10 a.m., the two have what is probably the most difficult conversation of their lives with their children. Jay with his three siblings. Foto: Annabel Clark / The Washington Post But even as the Taylors weep, there is jubilation on the internet. Those celebrating the death of Jay Taylor belong to the sadistic online group "764,” named for the first digits of the zip code of the 15-year-old Texan who started it in early 2021, a few months before Jay Taylor’s death. The group seeks out unstable minors to drive them to severe self-harm. The members feign friendship, then manipulate, threaten and blackmail their victims to drive them to increasingly drastic acts of violence against themselves. On camera. This article appeared previously on Substack. For our most up-to-date features, analysis, interviews and investigative reports, head over to "The German View" – from DER SPIEGEL on Substack. All you have to do to get early access is subscribe! Get it delivered straight to your inbox or follow us on Substack. Leslie and Colby Taylor did not initially know that Jay Taylor had been forced to film his own death. He was one of the first victims of the scene, which remains active today. He had been pressured into broadcasting his death live on Instagram. For the members of "764," such recordings count as trophies. For some of them, a livestreamed suicide is the ultimate goal. "Someone killed themselves on camera because of me," reads an online posting about Jay's death that DER SPIEGEL has obtained. "Let me know if you want the video." The Hamburg public prosecutor's office believes that a "764" user from Hamburg is responsible for Jay Taylor's death. Notorious in the scene, his name is Shahriar J., and he was 17 years old at the time. Operating under the name "White Tiger," he is thought to have been one of the ringleaders. The logo on a "White Tiger" account. Some accounts only vanished from the internet several months after his arrest. Foto: DER SPIEGEL J. was only taken into custody more than three years after Jay Taylor's death – arrested in a posh residential building in eastern Hamburg. He is alleged to have committed over 200 offenses against more than 30, mostly underage victims. He stands accused of possession of child pornography, serious abuse of several minors and young adults via the internet and five counts of attempted murder, among other infractions. The most serious is the murder charge in Jay Taylor's case. Shahriar J., now 21 years old, is in pretrial detention, with court proceedings in the juvenile chamber of the Hamburg Regional Court scheduled to start in early January. He is considered innocent until proven guilty. It is an unprecedented investigation in Germany, and possibly worldwide. It was only through Jay Taylor's death that the police began to uncover the extent of the violent crimes that "764” are suspected of having committed. Officials across the globe have begun investigating the network and continue to uncover a stream of abhorrent crimes. Investigative authorities believe that the network has contacted and harassed thousands of children around the world, with the FBI alone having opened over 300 cases in the United States. In Germany 10 of the country’s 16 state criminal police offices are investigating. The threat extends far beyond the "White Tiger" case. The "764" group is part of the "Com" network, which stands for "Community” – a global network of human hatred, a sadistic online scene whose members believe they can control and remotely manipulate their victims like characters in a video game. A logo used by the sadistic group "764." Foto: DER SPIEGEL A photo from the chat: Almost every form of violence is celebrated in the chats. Foto: DER SPIEGEL DER SPIEGEL has obtained thousands of messages from "White Tiger" and millions of chat posts from the "Com" network. What they show is almost too much to bear, the torment of the victims unimaginable. In order to illustrate this new online danger, DER SPIEGEL has chosen to describe at least some of the details. Our analysis has revealed that the network includes thousands of members, including dozens of subgroups. Still today, individual chat groups reach more than 1,600 members. Beyond the suspected murder of Jay, DER SPIEGEL has examined six other cases in which members of the scene drove people to their deaths. The number of unreported cases is likely to be significantly higher. In most instances, the victims committed suicide in a livestream, as in the case of 25-year-old Samuel Hervey. In one case in Leipzig, authorities are investigating suspicions that a "764" user caused a 13-year-old girl to stab her seven-year-old sister. Police found disturbing messages on the 13-year-old's device. Investigators say the general tenor of those messages was: "We know where your family lives, and we know all your family members. If you don't do what we say, we'll kill you all." DER SPIEGEL, which reported this story in collaboration with the Washington Post , has spoken with Leslie and Colby Taylor on several occasions since the arrest of Shahriar J. "If we didn't tell Jay's story, we would be doing an injustice to the indescribable loss," says Leslie. "I want to tell our story to warn other families." To enable DER SPIEGEL and the Washington Post to tell the story, the two have chosen to speak publicly in detail for the first time about how they fought to save their son. The Taylors made Jay's laptop and phone available to DER SPIEGEL, making it possible to analyze numerous online accounts that Jay had used before his death. Jay's devices that were seized by the FBI for the investigation and later returned to the family. Foto: Annabel Clark / The Washington Post "The world must know how dangerous '764' is," says Colby Taylor. "We did everything we could for Jay, we had all the resources, and yet we couldn't save him." For Jay Taylor, the internet was a social place. Just one day before his death, he used the Discord app to chat with other teenagers. Discord is used by 200 million people worldwide and is especially popular with gamers and young people. But Jay was not a gamer; he was looking for someone to chitchat with when he opened his gray Chromebook laptop in the living room that Sunday. "I had a sudden urge to get a pen pal," he typed. Under musical tastes he noted: "Folk punk, Midwestern emo, stuff like that." He would prefer someone between the ages of 13 and 15, he wrote, and someone who was queer, like him. "If you're interested: My inbox is open." Logos of the online platforms Discord and Instagram: "My inbox is open." [M] DER SPIEGEL; Foto: Valentin Wolf / imagebroker / IMAGO "Jay loved talking with other young people online," his mother recalls. He crocheted competitively with others in livestreams and liked chatting with peers. In the chats available to DER SPIEGEL, Jay was curious and empathetic. When someone wasn’t doing well, he would ask how he could help. Together with his mother, Jay had an account on the crafts platform Etsy. He was artistically talented and a good drawer, and he also crocheted and knitted, selling his creations online. "He always sold the things way too cheaply. I think he just wanted to make others happy," says Leslie Taylor. Jay was born a girl, but at the age of 10, he told his mother that he wanted to live as a boy. "His biggest worry was what others would think," Leslie recalls. Jay came out step by step, first telling his friends and family that he was gay, and only later daring to say that he was transgender. On the internet, Jay joined support groups for LGBTQ+ and trans children. He found the community helpful, say his parents. Jay's mental health problems began during the coronavirus pandemic. He struggled with anorexia and depression, and when he was 12 years old, his mother began noticing wounds on his skin. "The cutting was scary," says Leslie. But Jay made no secret of his difficulties and spoke openly with his parents about them. Together they learned that self-harm is not necessarily suicidal, but can be a coping mechanism – a response to psychological stress and strain. Images of Jay in the family's photo album. Foto: Annabel Clark / The Washington Post Jay’s parents sought help for him at a children's hospital in nearby Seattle. He started therapy and spent several weeks in residential treatment programs, as substantiated by medical records. Toward the end of 2021, Leslie and Colby Taylor began seeing improvements. Videos show Jay happily participating in a snowball fight with his brothers shortly before Christmas. "Jay was looking forward to going back to school and seeing his friends there," Leslie says about the weeks immediately preceding his death. But what they had found on Jay's computer worried his parents. Jay had spent some time in groups for self-harm on Discord – not brutal groups like "764,” but teenagers struggling with similar mental health problems and seeking help. ( This article - in German - provides tips for parents on how to protect their children .) Leslie and Colby Taylor in their child's bedroom. His creations are still on display. Foto: Annabel Clark / The Washington Post Jay knew that the net was not always good for him, his parents say. "’I need you to watch me. I need you to take my phone.’ He’d tell us things like that," Colby Taylor recalls. "We couldn’t explain the roller coasters." The parents had set strict rules to protect Jay online, including establishing how long he could use which apps on his phone and computer, and they would also sometimes delete Discord servers from his account. Furthermore, he was only allowed to surf the internet in the family's living room. "The tragic thing is that Jay sought support and affection on the net. In a vulnerable moment, he ultimately encountered exactly the opposite," says Leslie Taylor. An urban villa in the Hamburg district of Marienthal, designer furniture behind the floor-to-ceiling windows. Shahriar J. lived in this new building together with his parents. It is from here that he is thought to have committed many of his alleged crimes as "White Tiger." Just five days after Jay Taylor’s death, he is alleged to have caused a 13-year-old girl from Hamburg to carve a heart into her skin. For him. He has been accused of urging a 14-year-old Canadian girl in 2021 to painfully insert sharp objects vaginally and anally on camera. In hours-long chats, he is alleged to have convinced her that he was her steady boyfriend while simultaneously reinforcing her suicidal thoughts. He is alleged to have caused a 12-year-old girl from Northern Europe to kill a bird and arrange its dismembered body for a photo. Three hours later, "White Tiger" watched as she was forced to play tic-tac-toe with her own blood in a livestream on Discord. When she told him the next day that she wanted to leave Discord and lead a normal life, Shahriar J. is alleged to have first pretended that he would never again pressure her to cut, only to then urge her to commit suicide a short time later. For more than two years, J. is alleged to have continued to threaten and harass the girl according to the Hamburg public prosecutor's office, even when she was in a psychiatric clinic. DER SPIEGEL knows her identity, but because she is still a minor and to protect her from other "764" users, she shall be called Eva in this story. "He destroyed her self-esteem," says her lawyer. "She was too young to recognize how much control he had over her life." Another girl who chatted with "White Tiger,” in talking about his manipulation strategy, said: "He was sometimes very nice, and then he would be mean and creepy." DER SPIEGEL has obtained thousands of chat messages from "White Tiger.” They show that he apparently considered extreme online transgressions to be normal. He referred to himself as a racist and Nazi, and he wrote that he was a pedophile and "proud of it." He bragged about the pictures showing that girls had carved his username into their skin. "When I see someone humiliate themselves, it turns me on," he wrote. When he argues with others in the chats, it is about who has the more drastic depictions of violence on their computer. He also regularly wrote about his alleged drug use. In describing himself, he wrote: "I go to university, I work out, I go outside, I'm getting my driver's license, I study." And: "In my free time, I consume child pornography." Although "White Tiger" always wrote under a pseudonym, he did reveal a surprising amount about himself. He wrote that he was born in Iran and now lived with his wealthy father in a city in northwestern Germany. Once he even inquired about techno raves in Hamburg that he apparently wanted to attend. This fits with what a classmate of Shahriar J. tells DER SPIEGEL. J. was rather shy and sat together with the nerds, she says. But when he learned that she had once harmed herself, he questioned her at length. "He wanted to know why someone would do something like that and was very curious," says the woman, now in her early 20s, whose identity is known to DER SPIEGEL. When she was in 10th grade with J., she said she saw him publish a nude picture of a young girl for his Instagram followers. She confronted him, but J. responded by claiming that the girl had wanted him to post the picture. "It’s so normal. I have over 1,000 nudes of, like, 14 to 18," he wrote to her on the Instagram account that he operated with a fake profile picture. But the pictures were "not hot at all if my name isn't on them," he added. Shahriar J.'s parents apparently knew nothing about all this. DER SPIEGEL spoke with them in January 2024, when reporters sought to confront Shahriar J. with his online activities but only found his parents at home. During that encounter, his father, the Iranian-born CEO of a successful company, and his wife essentially said that their son must have clicked on the wrong thing on the internet. The father explained he would be unable to control everything the son did on the net. The father and mother are both thought to be currently struggling with their psychological health. DER SPIEGEL has learned that police have also conducted a search of the home of Shahriar J.’s brother. Christiane C. Yüksel, Shahriar J.'s lawyer: "We need to talk about the lack of regulation of online platforms." Foto: Bettina Theuerkauf / DER SPIEGEL Prior to his arrest, J. declined to answer questions submitted by DER SPIEGEL on several occasions. Today, he has his lawyer speak for him. When approached for comment, Dr. Christiane C. Yüksel said that she considered the murder charges to be "not tenable." She also said that it would hardly be possible for her client to have exerted influence on the 12-year-old girl from Northern Europe during the girl's clinic stays, as has been alleged. "I will not comment on the individual points of the indictment before the start of the main trial." The defense of her client would take place in the courtroom, she says. She does say one thing, though: "We need to talk about the lack of regulation of online platforms that networks like '764' can apparently use with little interference." Since the very beginnings of the internet, there have been niches in which extreme violence is celebrated. In the early days of the World Wide Web, images of mutilated corpses or texts about serious abuse were distributed in decentralized Usenet forums. Photos had to be sent divided into several text blocks because of the slow connections. In the late 1990s, so-called "shock sites” emerged, on which users would watch videos of serious accidents, suicides or videos of ISIS beheadings. Teenagers were considered particularly active users of such sites. At the same time, a pedo-criminal scene emerged in the darknet, uploading huge numbers of videos showing the most serious abuse. With "764," a new form of digital brutality has emerged in the social media age. Violence is no longer just consumed on the net, it is produced. Nowhere is this clearer than in the tutorials that members of the "764" scene send each other, bearing names in the vein of "Handbook for Sex Extortion" or "Suicide Tutorial." They describe in detail how to "recruit" new victims on the net and how to conduct conversations. The "764" users recommend approaching especially vulnerable and psychologically unstable minors. New victims, they say, can be found on the gaming site Roblox, which has millions of users, or on Discord. Perpetrators should make victims believe that they have many common interests, a guide explains. First, one should feign friendship or even love, then get the victims to undress on camera. To properly blackmail a girl, you need her address and nude pictures, the guide continues, one of the tactics employed by "764.” In the next step, you should threaten to send the recordings to parents or friends, it says. Threatening victims in such a manner, the guides say, put them under the perpetrator’s full control. The perpetrators are clearly intoxicated by their power and the violence they control remotely. As a perpetrator, they explain in one of the guides, you will never have to watch porn with restrictions again, since you can transform your victims into your own porn, controlled by you.” It is an invitation to prey on people online. And anyone can participate. "White Tiger" boasted that he had a "PDF with suicide instructions" on his computer. He had it in order to "help the emo girls." In the misanthropic logic of the "764" groups, this likely means: to drive them to suicide. For the Hamburg public prosecutor's office, those instructions play a central role in Jay Taylor's death and in the investigation against Shahriar J. To "live out his killing fantasies," J. is alleged to have enlisted the 12-year-old Eva as an accomplice and sent her several guides. Prior the night of Jay Taylor’s death, J. is alleged to have tortured Eva for over the course of seven months and made her "compliant." To the point that she allegedly followed his instructions to such an extent that he could make her help him out in an abhorrent act. It was Eva who first contacted Jay Taylor, the 13-year-old from Gig Harbor near Seattle. She had apparently found him in a group for people who struggled with self-harm. For Eva, located in Northern Europe, it was Monday morning; for Jay, on the West Coast of the U.S., it was still the middle of the night when she wrote to him on January 17, 2022. First, she is thought to have sent Jay one of the suicide instruction manuals that she had previously received from "White Tiger," then the two chatted on Discord. Eva, as the partially archived chat messages suggest, apparently exerted pressure on Jay to kill himself. Two and a half hours after the start of this Discord chat, Jay was dead. Still today, the more than three dozen messages that Jay sent to Eva can be found on his device. Three times during the conversation, Jay insisted that he did not want to kill himself. By then, he had left the self-harming groups and chats on the platform. "i got some stuff going on that i want to live for," he wrote around 2:15 a.m. He apologized that he no longer wanted to harm himself and would not comply with Eva's request. Eva later deleted her part of the conversation – apparently out of panic. As such, it cannot be precisely reconstructed how she succeeded in persuading Jay to commit suicide. But according to the Hamburg public prosecutor's office, she exerted pressure on Jay using a trick that was in one of "White Tiger's" instruction manuals: She pretended that she wanted to kill herself together with him. She apparently called herself his "suicide bestie." An investigator familiar with the case believes the girl acted in this way out of fear that she would have to kill herself for Shahriar J. "A live-streamed suicide was the one thing she didn't want to do for 'White Tiger.'" To appease him, she apparently wanted to supply him with another victim. "Just don’t kill yourself without me," Jay wrote at half past two in the morning. " "If your gonna, do it dm (direct message) me and ill do it with you, preferably not tho.” Half an hour later, Eva had finally changed Jay's mind. Jay then snuck out of the house, past his sleeping mother, grabbing a white extension cord on the way out. At the same time, Eva opened a group on Instagram in which the suicide was to be broadcast live. She added "White Tiger" to the group and named the call in such a way that it indicated that Jay would die. The title also contains the expression "LMAO,” a common online chat abbreviation meaning "laughing my ass off.” DER SPIEGEL is in possession of the video, but to prevent its distribution, we have decided to refrain from mentioning the chat’s full name. When the Instagram call finally began, Shahriar J. is alleged to have taken over the conversation. He used the same account through which he had also chatted with his classmate over half a year earlier. At that time, J. was sitting in the gaming department of the Saturn electronics store, in the multi-story branch near Hamburg's main train station. On his phone, he followed what was happening from 4:36 a.m. local time in Gig Harbor. At that time, Jay Taylor was standing behind a supermarket, about a 15-minute walk from his home. A few meters away from garbage containers and the store's truck loading ramp, he positioned himself in front of a chain-link fence. "Do you have a rope?" Shahriar J. allegedly asked. He demanded that Jay undress. "It’s hotter," he wrote in the chat made available to DER SPIEGEL. But Jay kept on his black and white T-shirt and placed his iPhone 6 on the ground in front of him. He positioned it so that it filmed his face and upper body. He tied the white extension cord he had brought to the fence. Then he put a noose around his neck. While Jay fought for his life, more users joined the livestream. Six minutes later, Jay was dead. His tormentors made fun of him afterward in the chat, insulting him with transphobic comments and writing that he deserved nothing less. Shahriar J. appears to complain about the bad camera, resulting in a poor recording quality. Still, he saved a copy of the video for himself. He was apparently aroused by what he saw, according to the public prosecutor's office. All this may never have become widely known without a girl from Australia. "I decided straight away I need to do something about this," says the teenager of the moment she first encountered the video. People from the "764" scene had previously tried to drive her to suicide as well, she says. She secured the chats on Discord and Instagram, found one of Jay's school friends and got Jay's father Colby Taylor's Instagram contact from him. " I’m not sure how much you’ve been told," she wrote to him six days after Jay's death. "They need to be stopped." She then sent him a list of Discord usernames and added: "I'm so sorry you have to see this too." When Colby Taylor received the message from the Australian teenager with the video, he locked himself in the bathroom so his wife wouldn't see it. He recognized his son's black and white striped T-shirt. He saw the extension cord noose. He stopped the video. He forwarded the video and all the other evidence to the local police department in Gig Harbor. Only then did investigators realize that there was more behind Jay's death than a suicide. They brought in two FBI investigators. It was the beginning of the investigation into Shahriar J. But it would take until June 17, 2025, before German police finally stormed his apartment in Hamburg-Marienthal at 3 a.m. and arrested him. Since then, Shahriar J. has been locked in a cell in a juvenile correctional facility in northern Germany. The prison administration has put him in a solitary cell away from other inmates – apparently because they do not know how other prisoners might react to him and because of his manipulative nature. Not entirely without reason, as shown by messages that two of his victims have apparently sent to him in prison. As a person familiar with the proceedings told DER SPIEGEL, the two still seem to feel a strong connection to him. Despite the fact that J. is thought to have abused both girls for months beforehand. Jay Taylor's gravestone. Foto: Annabel Clark / The Washington Post In the city-state of Hamburg the case became a political topic. In mid-November, Jan Hieber, head of the Hamburg State Criminal Police Office, faced questions from Hamburg politicians about the investigation and told them that future investigations against particularly dangerous perpetrators needed to be prioritized and accelerated. Shortly after J.'s arrest, DER SPIEGEL reported on indications that Hamburg authorities had failed to recognize the scale of the "White Tiger" case for almost two years. FBI agent Pat McMonigle became frustrated with the slow pace of Hamburg authorities after he uncovered "White Tiger" with a fellow agent. Foto: ABC News FBI investigator Patrick McMonigle, who managed to discover Shahriar J.'s identity not long after Jay Taylor's death, has been critical of the fact that the investigation took unnecessarily long. As early as February 2023, more than two years before the arrest, he and his FBI partner, he says, handed over their investigation results, including Shahriar J.'s true identity, to Hamburg authorities. And even back in 2021, Hamburg police received written information from a U.S. organization fighting child abuse that Shahriar J. was a member of "764" and was trying to pressure underage victims to commit suicide. Even then, the Americans pointed to two victims whose cases are now part of J.’s indictment. Shahriar J. confessed to possession of youth pornography at the time and the case was dismissed in 2021. The case has also attracted political attention in the U.S. Colby Taylor plans to fly to the U.S. capital Washington in mid-December and potentially testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee. As a result of his son’s death, lawmakers intend to hold the heads of platforms like Discord accountable for their alleged lack of protective measures. Colby Taylor has sent the Senate committee an 11-page legislative proposal. He has been working on the regulation, which he has called "Jay's Law,” since he learned the extent of "764" through Shahriar J.'s arrest. He is demanding the introduction of a separate criminal offense for digital coercion and extortion resulting in death. And tech platforms like Discord should be required to introduce an emergency button that ensures that human employees review a potentially dangerous conversation within 15 minutes. Jay Taylor's father Colby with the doily made by his son. He carries it with him in his backpack. Foto: Annabel Clark / The Washington Post As always when he is traveling, he will have a small, knitted doily in his backpack. Jay made it for him a couple of months before his death. When he speaks about it during his conversation with DER SPIEGEL, he pulls the purple doily out of his backpack and holds it up to his nose. It still smells like Jay, Colby says.

WorldWorld

The "White Tiger" Case: How an Online Search for Friends Ended in Coerced Suicide

Loading article...

AI Index

Neutral / Balanced

Facts presented without strong bias.